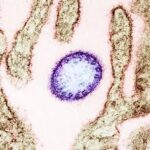

Nipah virus is a rare but highly lethal zoonotic pathogen that has drawn renewed global attention because of its high fatality rate, capacity for human-to-human spread, and the current absence of licensed vaccines or proven antiviral treatments. Understanding how Nipah spreads, recognizing early symptoms, and following clear prevention measures are essential for protecting communities in affected regions and reducing the risk of wider outbreaks.

Nipah was first identified in 1999 during an outbreak among pig farmers in Malaysia and Singapore, where severe respiratory illness and fatal encephalitis were reported. The virus is naturally hosted by fruit bats of the Pteropus genus, commonly called flying foxes, which can shed the virus in saliva, urine, and feces. These bats can contaminate food sources or infect intermediate animals such as pigs, which then amplify the virus and increase human exposure. Fruit bats, contaminated food, and infected domestic animals are the primary pathways that bring Nipah into human populations.

Symptoms typically appear within four to 21 days after exposure, though longer incubation periods have been recorded. The illness often begins with sudden fever and flu-like symptoms that can rapidly progress to severe respiratory disease and neurological complications such as encephalitis or meningitis. Encephalitis is the most dangerous complication and is associated with a very high risk of death; survivors may suffer long-term neurological problems including seizures and personality changes. Health authorities estimate case fatality rates ranging widely, with many outbreaks reporting mortality between 40 and 75 percent.

Human outbreaks have been geographically concentrated in South and South-East Asia. Bangladesh has reported cases almost every year since 2001, India has experienced repeated outbreaks including in Kerala, and earlier large outbreaks occurred in Malaysia and Singapore. Antibodies to Nipah have been detected in bats across broader regions including parts of Africa such as Ghana and Madagascar, but human outbreaks outside South and South East Asia have not been recorded to date. This geographic pattern highlights both the localized nature of most outbreaks and the potential for wider spread where ecological and human-animal interfaces permit.

Transmission to humans most commonly occurs through direct contact with infected animals or by consuming food contaminated by bat secretions. A well-documented route is the consumption of raw or partially fermented date palm sap, which can be contaminated when bats feed on or lick sap collection sites. Person-to-person transmission has also been documented, particularly among family members and caregivers in close contact with infected patients, especially those with respiratory symptoms. Close caregiving, inadequate infection control in healthcare settings, and cultural practices involving raw foods are key drivers of human spread.

There is currently no licensed vaccine or specific antiviral therapy for Nipah virus infection. Clinical management focuses on intensive supportive care for severe cases. Research efforts are underway worldwide to develop vaccines, monoclonal antibodies, and antiviral drugs; several experimental therapies are in early clinical trials. Because of its high mortality and pandemic potential, the World Health Organization has classified Nipah as a priority pathogen requiring urgent research and development. Public health agencies such as the UK Health Security Agency have also designated Nipah a high-priority pathogen and are investing in diagnostics, treatments, and international response capacity. The absence of approved countermeasures makes prevention, early detection, and rapid outbreak response the most effective tools available today.

Practical prevention measures that reduce risk at the community and individual level are straightforward and evidence-based. Avoiding contact with bats and sick animals, refraining from consuming raw date palm sap or other foods that may be contaminated by bats, practicing rigorous hand hygiene, and using protective equipment when caring for sick people are proven ways to lower transmission risk. In outbreak settings, strict infection prevention and control in healthcare facilities, safe burial practices, and rapid case isolation are critical to stop chains of transmission. Public education campaigns—especially in rural and semi-rural communities where human-animal contact is frequent—have been effective in reducing risky behaviors and protecting children and families.

For travelers, the overall risk remains low if basic precautions are followed. Visitors to affected regions should avoid contact with bats and sick animals, do not consume raw or unprocessed date palm sap, and seek medical attention promptly if they develop fever, respiratory symptoms, or neurological signs during or after travel. Health authorities emphasize that routine travel restrictions are not typically necessary for most travelers, but staying informed about local outbreaks and following public health guidance is essential. Travelers who plan to visit rural areas or engage in activities that increase contact with wildlife should take extra precautions and consult travel health professionals before departure.

Public health preparedness requires coordinated investment in surveillance, rapid diagnostics, and community engagement. Early detection of cases through strengthened laboratory networks and surveillance systems enables faster containment. Training healthcare workers in infection control, equipping hospitals with appropriate protective gear, and supporting local education programs—such as school-based initiatives that teach children how Nipah spreads and how to prevent infection—are practical steps that reduce outbreak impact and protect entire communities. International collaboration, funding for vaccine and therapeutic research, and rapid deployment of response teams are also essential to prevent localized outbreaks from escalating into larger epidemics.

Media coverage and public messaging should balance urgency with accuracy. Sensational headlines can cause unnecessary panic, while underplaying the risk can delay protective actions. Clear, consistent communication that explains what Nipah is, how it spreads, what symptoms to watch for, and what concrete steps people can take will save lives. Authorities and journalists should prioritize verified information from public health agencies and avoid speculation about unproven treatments or exaggerated transmission scenarios.

Nipah virus is a high-consequence pathogen with a history of deadly outbreaks in parts of Asia. Its natural reservoir in fruit bats, potential for animal-to-human and human-to-human transmission, severe neurological complications, and lack of licensed vaccines make it a global public health priority. Prevention through behavior change, community education, infection control, and investment in research and surveillance remains the most effective strategy to reduce risk and protect vulnerable populations. Staying informed, practicing simple hygiene and food-safety measures, and supporting public health preparedness are practical actions everyone can take to limit the threat of Nipah.

Source: What is Nipah virus and why WHO list it as a global epidemic threat – Graphic Online