Malaria remains a pervasive public health challenge in Ghana, with the entire population considered at risk and specific groups such as children under five and pregnant women facing higher vulnerability to severe disease due to lower immunity. Ghana is listed among the 15 highest-burden malaria countries in the world, accounting for 5.30 percent of malaria cases in West Africa, and in 2023 the country contributed 2.5 percent of global malaria cases and 1.9 percent of global malaria deaths, indicating that substantial reductions in burden are still required.

Recent trends show a concerning rise in case incidence, with malaria cases per 1,000 population at risk increasing by 22 percent from 159 to 193 between 2022 and 2023, while reported deaths per 1,000 population at risk remained relatively stagnant at 0.35 over the same period. Transmission in Ghana is perennial but seasonally variable across regions, with a six- to seven-month transmission window across much of the northern area and shorter three- to four-month seasons in upper northern zones, driven in part by distinct rainfall patterns that influence vector abundance and the timing of peak transmission.

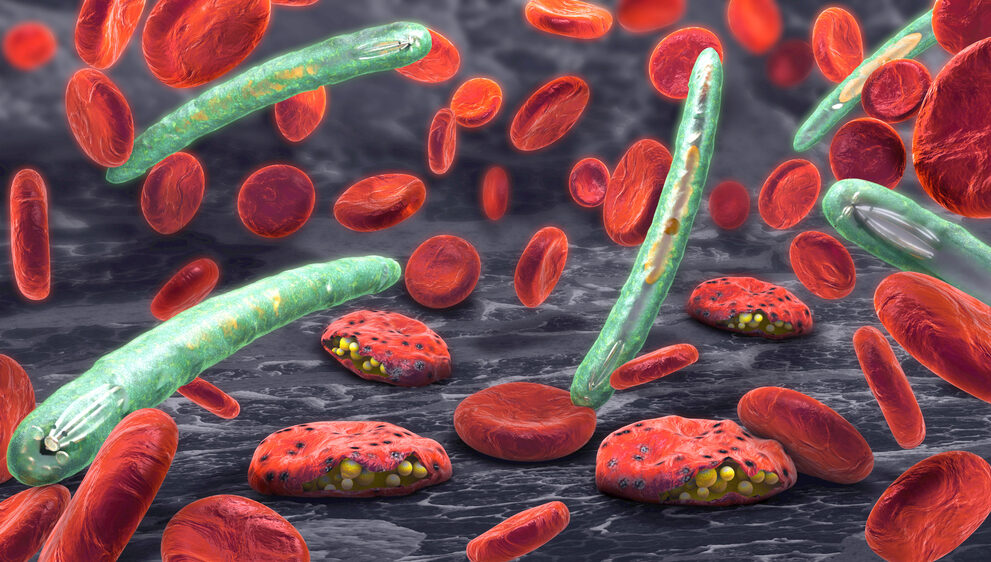

Plasmodium falciparum accounts for more than 90 percent of malaria infections in Ghana, with Anopheles gambiae and Anopheles funestus identified as the principal vector species contributing to transmission, which frames diagnostic, prevention, and vector-control priorities for national programmes. The national strategy combines vector control, chemoprevention, case management, community-level services, and surveillance, reflecting the multifaceted nature of malaria prevention and the need for coordinated implementation across health system levels.

Insecticide-treated nets (ITNs) form a central pillar of Ghana’s vector-control efforts, distributed through mass campaigns every three years, school-based programmes, and continuous channels targeting pregnant women and young children at antenatal and child welfare clinics. Access to ITNs has increased in recent years, rising from 67 percent in 2019 to 76 percent in 2021 and 79 percent in 2022, although uptake and use exhibit urban-rural disparities, with lower use-to-access ratios in urban and peri-urban settings where preferences for alternative mosquito-control methods and practical challenges with net hanging affect redemption rates.

Indoor residual spraying and ITN acceptance remain operational challenges in many communities, and the programme has adapted its distribution approach to better match user preferences in urban contexts, including reducing the number of rectangular nets planned for urban households in the 2021 mass campaign where hanging constraints and behavioral choices were evident. Ghana’s programme has also emphasized that ITN use among high-risk groups has improved, with net use among children under five rising from 22 percent in 2006 to 54 percent in 2019, and use among pregnant women increasing from 20 percent in 2008 to 49 percent in 2019.

Drug-based prevention strategies include intermittent preventive treatment in pregnancy (IPTp) offered at antenatal care and Seasonal Malaria Chemoprevention (SMC) for children aged three to 59 months in areas with highly seasonal transmission, implemented through door-to-door campaigns during peak months in the northern and savannah regions. Ghana achieved notable SMC scale-up in 2022, completing four cycles across 72 districts in seven regions and reaching about 1.45 million children, with estimated coverage near 90 percent of the targeted population, though barriers such as preference for traditional remedies, access constraints, and fear of adverse reactions remain.

Case management is governed by the updated national guidelines that prioritise prompt diagnosis and treatment across community, primary, secondary, and tertiary levels of care, stressing the importance of pre-referral treatment for severe malaria and the use of parenteral artesunate as first-line therapy for severe disease in hospital settings. Ghana follows the test, treat, and track approach to reduce misdiagnosis and improve outcomes, but progress in early care-seeking and treatment is hindered by negative experiences at health facilities, local beliefs about fever causes, and costs associated with testing and care, which point to the need for targeted social and behaviour-change investments to improve health-seeking practices.

Community Health Planning and Services (CHPS) and Integrated Community Case Management (iCCM) form essential delivery mechanisms for malaria interventions at the grassroots level, with CHPS compounds providing ACTs, IPTp, ITNs, rapid diagnostic tests, immunisations, family planning, and community surveillance, and with Ghana having expanded CHPS coverage to roughly 6,500 compounds covering nearly half the country by 2020. The CHPS model relies on community acceptance and leadership support, and accredited CHPS services are free for active national insurance card holders, making CHPS central to the country’s strategy for equitable access to malaria services.

Financing remains a critical determinant of programme sustainability and scale. As of 2017, less than a quarter of Ghana’s health spending came from national resources, and although the government planned to transition to locally funded procurement of malaria commodities under a “Ghana Beyond Aid” vision, procurement commitments have been inconsistent, with a default on the 2022 procurement plan and uncertainty about when government-funded procurement will fully resume amid economic constraints. Donor partners have continued to play a major role, with the Global Fund, the US President’s Malaria Initiative, and other partners contributing substantial financing, while the national government reported significant health expenditures in 2023 but still relies on mixed funding sources to maintain commodity supplies and programme operations.

Malaria in pregnancy remains a priority within national maternal health objectives, with Ghana adopting WHO-aligned guidance for antenatal contacts and IPTp dosing to ensure early access to prevention and to integrate malaria prevention with broader maternal and newborn care; the country achieved high coverage for IPTp two-dose uptake relative to the sub-Saharan region and has seen progressive increases in IPTp3 coverage, although challenges such as late antenatal attendance and provider attitudes limit full realisation of these interventions.

Looking forward, Ghana’s newly drafted National Malaria Elimination Strategic Plan (NMESP) 2024–2028 retains ambitious targets carried over from the previous strategy, aiming to reduce malaria mortality by 100 percent and case incidence by 50 percent by 2028 relative to the 2022 baseline, a goal that will require strengthened surveillance, sustained financing, expanded preventive coverage, and robust multisectoral action on drivers such as climate variability and environmental degradation that may alter malaria epidemiology. The plan recognises climate change, including shifts in rainfall and temperature and land-use changes, as emerging influences on transmission that will demand adaptive implementation of prevention and control tools.

The pathway to elimination in Ghana hinges on closing financing gaps, maintaining reliable commodity supply chains, enhancing community engagement and health behaviour interventions, strengthening facility readiness for clinical management, and investing in surveillance and laboratory capacity to ensure rapid detection and response to hotspots and seasonal surges. The combination of community-level service platforms such as CHPS and iCCM, expanded preventive campaigns like SMC, and improved vector-control coverage through ITNs and targeted IRS offers a comprehensive toolkit, but delivering these interventions at scale and with quality will depend on predictable domestic funding and coordinated partner support.

Ghana’s malaria story is thus one of progress paired with persistent vulnerability: measurable gains in net access, strong IPTp performance, and effective SMC campaigns coexist with rising case incidence, financing shortfalls, and operational barriers to universal coverage. The country’s elimination ambitions will require political will translated into budgetary commitments, data-driven targeting of interventions, and sustained investment in the health system’s capacity to prevent, detect, and manage malaria at community and facility levels.

Source: Multi-country outbreak of cholera, external situation report #30 -26 September 2025